Charity M.

Moore and Matthew Victor Weiss

Journal of Ohio

Archaeology 4:39-72, 2016

An electronic

publication of the Ohio Archaeological Council

Abstract:

Rock piles are some of the most ambiguous features encountered in the Upper

Ohio Valley, encompassing diverse origins and functions. A single pile can

appear to be consistent with multiple interpretations and each interpretation

carries implications for how the rock pile is then recorded (or not recorded)

and evaluated against the National Register of Historic Places criteria.

Building on recent fieldwork at the Bear Knob Rock Piles (46UP342), this

article explores historical sources, regional case studies, and archaeological

methods that can be used to examine rock features, and calls for the adoption

of similar best practices and guidelines at the federal and state levels. Only

through a comprehensive, programmatic approach, informed by indigenous

knowledge, can archaeologists overcome the ambiguity of rock piles and expand

their understanding of the ways people augment and interact with the landscape

through the construction of rock features and the material affordances of

stone.

Some excerpts:

“Most other

SHPOs across the country also reported dealing with rock features on a

relatively regular basis (Table 2), and a small number of archaeologists are

actively researching the topic through the compilation of data on known rock

features and new excavations (e.g., Holstein 2010; Holstein, Hill, and Little

2004; Loubser and Hudson 2005; Loubser and Frink 2010; Murphy 2004, 2010;

Rennie and Lahren 2004). Despite this, our understanding of rock features as a

whole has not significantly progressed beyond Kellar's 1960 publication...”

“... The

issues described above have had another unfortunate side effect. In our

experience, members of the public who are confronted with the apparent

antiquity and visually impressive nature of rock features often become

frustrated with their dismissal by professional archaeologists, or by

archaeology's failure to explain their origins. As a result they often turn to

pseudoarchaeological or mystical explanations. These features' ambiguity

creates an ideal situation for theories about extraterrestrials, lost

civilizations, and supernatural entities to flourish, as people try to make

sense of these landscapes. However, this ambiguity has not stopped many

avocational and amateur archaeologists, historians, and other researchers from

conducting insightful and thorough research on cairnfields, rock effigy sites,

and other stone landscapes. Although some interpretations may not be based on

conventional science, history, or archaeology, the many websites, blogs, and

articles resulting from this public interest contain a wealth of primary data

that are invaluable to the archaeological researcher (e.g., NativeStones.com

2006; Waksman 2005, 2015; and see Muller 2009:17). Rather than belittling or alienating

non-archaeologists, we should encourage public interest in archaeology and

coordinate our efforts to understand the past. In fact, our literature review

demonstrates that the most comprehensive, ongoing rock feature research in the

northeastern United States is not being conducted by professional

archaeologists. The websites and publications of the New England Antiquities

Research Association (NEARA 2015; see Ballard and Mavor 2006; Holstein 2012;

Muller 2009), a group of primarily "amateur" rock feature

researchers, and of historian mother-and-son team Mary and James Gage (J. Gage

2014; M. Gage 2015; M. Gage and J. Gage 2009a, 2009b, 2015; J. Gage and M. Gage

2015b) are far more comprehensive than the vast majority of modern

archaeological publications. The Gages alone have filed more than 50 rock

feature site forms in Rhode Island and Connecticut. The results of such

long-term research should not be discounted simply because individuals do not

hold academic degrees in archaeology or work in CRM, particularly when these

individuals are the ones who try to reach out to professional archaeologists

(see Muller 2009). As Mary Gage (personal communication 2016) pointed out,

historians are often better qualified to conduct certain aspects of rock pile

research, such as analyzing primary documents...”

I appreciate the shout out.

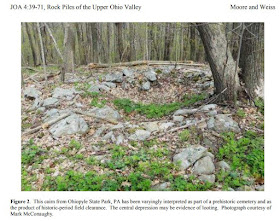

ReplyDeleteAnd...Good Lord!...do you see that pile with a hollow? That is the money.

ReplyDeleteThe "shout out" is a bit condescending - talking about people without academic credentials. As it turns out, some of us have PhD's that we don't wave around.

ReplyDelete